Wartime Remembered

INTRODUCTION

This book entitled "Wartime Remembered” is the third publication of the Baildon Oral History Group since its foundation in 1983. The two previous books “Our Village - Loved and Remembered” and High Days & Holidays were much appreciated and full of interest to people.

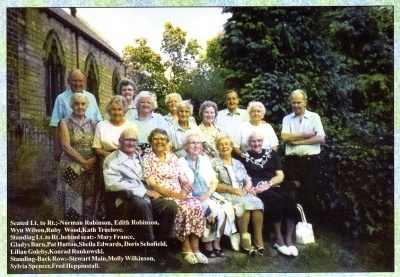

The new publication is as a result of more than a year's work, and whilst it is chiefly concerned with people's memories of Baildon in the Second World War, some contributions are from people who did not live in Baildon at the time but moved here after the war. We are indebted to all members and everybody who lent the group photographs and other documents especially Arthur Edwick and Konrad Ronkowski. We are grateful to Rosemary Cole for proof reading the text and Sylvia Spencer for working at the printers on design and editing. The members of the group often found talking about wartime sad, but full of amusing incidents arising from the changed situations. Friends and relations were killed and the loss surfaces many years later.

Stewart Main 2000

The group was composed of the following members:-

Gladys Burn

Sheila Edwards

Mary France

Marjorie Gardiner

Lilian Goleby

Fred Hep‘pinstall

Pat Hutton

Stewart Main

Edith Robinson

Norman Robinson

Konrad. Ronkowski

Doris Schofield

Sylvia Spencer — Editor

Kath Truelove

Wyn Wilson

Molly Wilkinson

Ruby Wood

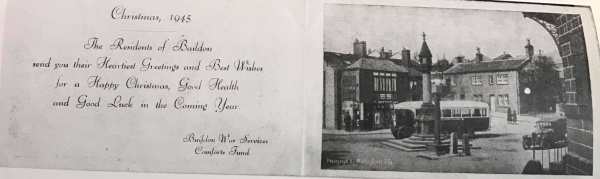

- Front Cover-Baildon War Memorial (photo Fred Hutton)

- Inside Front Cover-Baildon Oral History Group - Moravian Church Grounds

- Inside Back Cover—Personal Message from Queen Elizabeth

- Back Cover—Tong Park War Memorial (photo Fred Hutton)

Mary's Memoirs

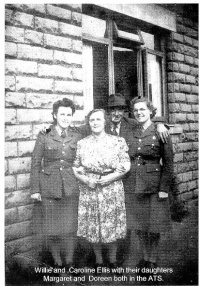

by Mary K France (nee Ellis)

There had been an uneasy peace during 1938-39 and I was not surprised when an employee of Charlestown Dyeing Company where I worked came into the office to report that, being in the Territorial Army, he had received his call-up papers and would therefore be leaving work. Gradually more and more young men went and women filled their places in industry and on the land.

The Carnival of September 1939 had been in full swing for six nights when on Saturday 2nd September a complete blackout was ordered and the activities arranged for that night were transferred to the Moravian Sunday School, suitably blacked-out. This was very disappointing for the young ones, but considered necessary by the "Powers that Be".

Little did we know on that fateful 2nd September night, that the Carnivals as we had known them were gone for ever; no more fairy lights to illuminate our carefree nights of dancing, concerts, brass bands and fun. Our immediate future years were to be filled with activities of which we never dreamed and which would take many of our number into far-flung parts of the world, some sadly never to return. The Germans occupied the Channel Islands and many women and children were evacuated to Baildon. They were warmly welcomed and some remained here after peace was declared.

On the night Bradford was bombed two friends and I were on our way home from a dance at the Presbyterian Church in Symes Street, Bradford when we saw flashes and heard the 'crump' of falling bombs. Our house in Westgate was the nearest refuge, so we dashed in and joined in the hurried preparations for shelter. My mother ushered us under the big oak dining room table, made us comfortable with cushions and the overflow went under the stairs. There we stayed 'til the wail of the "all-clear" siren. Some of the residents went to the Bank to view the countryside illuminated with the flames from the fire in Bradford.

The Odeon cinema was hit only ten minutes after the last patron had left; also part of Rawson Market and a large departmental store, Lingards, were destroyed. Gone were our treats of toasted tea cakes and tea after shopping, particularly in the lovely balcony cafe, accompanied by music from an elegant four piece orchestra. Robert's Pie Shop in Godwin Street also suffered a hit which took away for ever the mouth-watering window display of crusty meat and potato pie with steam rising.

We had an anti-aircraft battery stationed on the moor and often saw searchlights sweeping the dark countryside. Tanks also appeared on the moor and ploughed up part of it, until lay-bys were constructed. Future generations may well wonder why these were made.

I have many memories of the blackout. We could only carry a torch if covered with three layers of tissue paper and this meant, on pitch dark nights, walking home from work feeling with my feet to discover where the curb turned into various roads. The seats in the buses were removed and re-placed around the sides to leave more room for people to stand. There was a bonus though as the skies revealed a myriad of stars and the 'Bear' and 'Plough' were easily located, and shooting stars lit up the sky.

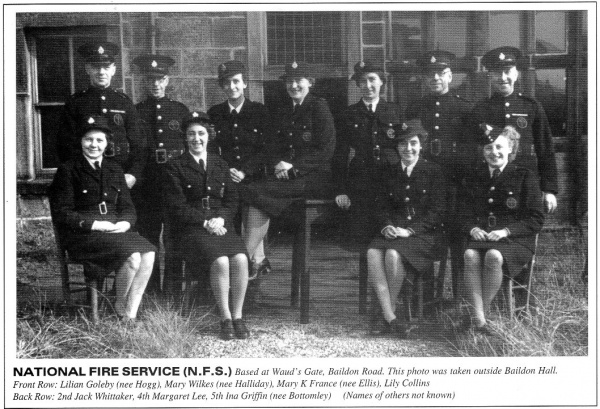

I was recruited into the Fire Services and served after working a full day in a firm producing Khaki, Air Force blue and Navy material for the Armed Forces. I reported every sixth night for duty at the fire station until morning and then back to work.

We also had to turn out every time the siren sounded during the night and it was most, uncanny to be hurrying down Baildon Road in the early hours of the morning, hearing the sound of scurrying feet of others going on duty, passing behind and in front but seeing none. In the violence of today it is difficult to believe that women had no fear of being attacked or robbed in the complete darkness.

Part of my duties was on the Fire Boat on the Leeds/Liverpool Canal looking for incendiary bombs. Some of us manned the canteens which the churches and YMCA ran for the comfort of the soldiers stationed in the village. They were billeted in The Picture House, Moravian and Primitive Sunday Schools, and larger houses. Those in the picture house went to sleep on the floor in the l/3d and woke up in the 4d. The seats had been removed leaving a very sloping floor. Scrambled egg was produced from reconstituted powder. Goodness knows how many pounds of baked beans and slices of toast were served.

One of my contemporaries tells me that she received a letter only recently enclosing a cheque. It was from a now elderly gentleman who was once one of those soldiers stationed in our village, who had come to realise how good Baildon people had been to him and other lads. We had happy times at dances in the Parochial Hall known as the 'the Paroche'. These were run by Scouts. The adults played whist nearby but kept an eye on proceedings. Most of the soldiers attended and there was no shortage of partners, but we had to develop the art of avoiding untrained feet. The band was called "The Blue Masqueraders”. The last number was always a waltz "Save the last waltz for me”.

Recollections of the day war broke out.

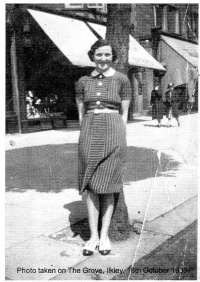

by Lilian Goleby (photo)

Sunday 3rd September 1939 we had decided to have a day out and go to the Yorkshire Coast. There was to be an important announcement on the wireless at 11am. Neville Chamberlain had been to Germany to talk, to try and achieve a lasting peace. This did not stop us going out so off we went. Everything seemed the same until we reached Tadcaster and this was our first sign of war. The police had blue tin hats on and gas masks slung over their shoulders and down the hill came tank after tank all from Catteriek. We wondered where they were going. As we arrived at each town all the police were wearing helmets. We did not see any more tanks, but it gave us a lot to talk and think about. We arrived home again in time to go to church at 6pm to pray for peace, which did not return for another six years.

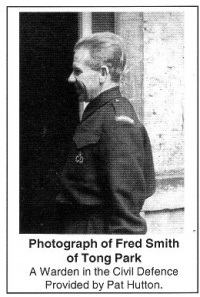

Us and the Air Raid Warden

by Pat Hutton (nee Smith ) (photo)

When the War started the Council reinforced our cellar for us to use as an Air Raid Shelter. As we lived in a very lonely house behind a private club at the end of a drive with allotments on one side and woods on the other, we didn't get many passers—by. This particular night we were in the cellar. The siren had gone and the German planes were going over. I don't know if any bombs had been dropped. Suddenly we heard heavy footsteps and Mother cried out "Oh they’ve landed." We all held our breath and then a voice shouted "Put that light out" it was an Air Raid Warden!

Mother had to go into the club and turn out the lights as the members had all dashed home without bothering about them.

Fred Remembers

by Fred Heppinstall. (photo taken at Lake Como, Italy 1944)

I worked at Denby's Mill when the war broke out. I remember when the siren sounded we had to go in the shelter which was a tunnel under the railway. Sometimes we would be there for two or three hours, as we had to stay until the "all-clear" sounded. We thought it was great getting paid for doing no work. However I left the mill and went to work for Murgatroyd's Bakers. I used to start work at four in the morning, in the bakehouse, until about eight o'clock. Then I would go out with the van on my round, which took me to all parts of Baildon. I enjoyed being out with the van very much. I met lots of people; one I remember very well was a milkman. We used to meet on West Lane leading to The Glen. He would give me a bottle of milk and in exchange I gave him a custard or an apple pie. I also used to go to the bakehouse on a Sunday morning and get the wood and coke ready for re-lighting the fire later the same night ready for an early start the next morning. My boss was very good to me giving me all the cakes and pies etc. which were left on Saturday to take home. We sure had some good tuck—ins.

Sadly these good times came to an end and I had to go into the forces. I went into the army in the service corps, did my military training, went on a course and became a cook. I got stationed in Bradford, which was very good for me because I lived in Baildon. I managed to get home nearly every day. I used to bring a load of soldiers on Saturday night to the Church Hall. We had some great times — one in particular when we were all doing the Hokey Cokey and the vicar called us to a halt. He said that if we didn't stop he wouldn't let us come again. When it was explained to him about all the money he would lose the man changed his mind.

I later got posted overseas and saw plenty of action in Sicily and Italy. Luckily I came through it all and here I am back with all my good friends.

The Robinsons’ Reflections

by Edith Robinson (nee Robinson)

Saturday, September 2nd 1939 was during another annual carnival week. Lights were strung across the streets and around the village centre, a platform was set up at the side of the Angel Hotel, and here usually every evening shows were given by both amateurs and professionals.

Usually the carnival opened at 2pm with a procession passing through the village and up to the tide field, which was at the back of what now is the 'Co-op/ Copper Beech car park’. Various attractions were held here until 5pm. The concerts in the village started at 7pm then at 10pm a band would play popular music and people danced in the village and young ones danced up Northgate towards the moors; buses which ran until very late were directed up Westgate.

This particular evening, there was an uneasy feeling in the air; Chamberlain had given Hitler an ultimatum to get out of Poland by 11am on Sunday September 3rd 1939. Sunday morning came, all was very quiet in the village, everyone was listening to the wireless wondering what they would hear. At last Chamberlain’s voice came over the air at 1 1am. "We have no reply from ' Germany so we are at war with Germany". I think a cold shiver went down everyone’s spine, and the carnival was immediately closed down.

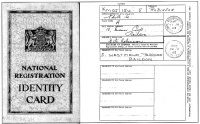

Germany had a big military force; what would happen now? Would they invade England? We knew all .. the young ones would be called into the forces, and the older ones to war work. Factories would have to change over to war work, such as making planes, tanks, rifles, uniforms and boots etc. for the forces. Air raid shelters would have to be built, England was blacked out, road signs were taken down, and no one had to show lights of any description when it became dark.

Housewives lined their curtains with black material, and anyone using flashlights had to have just a small hole in the centre, about 1/2" round. Air Raid wardens walked the streets at night; if anyone was showing a light, they were warned about it. Other men were on siren duty. Also formed were the volunteer ambulance service and fire brigade. People changed to war work, as the factories completed their change over. Things seemed quiet in the North, and we still visited cinemas, dance halls etc.

About this time [volunteered for war work, and left a dressmaking factory in Shipley to work at Crompton Parkinson in Guiseley. On the first morning, I was put on a machine making bullets. I found this very monotonous, especially after embroidering dresses and wedding veils. Just before dinner I was told to go to the office, the manageress wished to see me. I thought to myself, I must have been putting the bullets the wrong way into the machine. She said they were changing over from two shifts to three shifts, and would I like to be a storekeeper. I was delighted and immediately accepted, and was taken to meet the other storekeeper to be shown what to do. Periodically large lorries came to collect boxes of cases and bullets, which were then taken to Doncaster to be filled with gunpowder. Another part of the factory made electric motors which were dispatched to Russia. The three shifts meant I had to leave home at 5:15 in the morning, 1:15 in the afternoon, and 9:15 in the evening. Luckily I had a friend living nearby who worked at the same place so we walked down Old Langley Lane and caught the bus in Otley road. These were special buses which took us directly to the factory.

One night we were walking down Old Langley Lane in complete darkness, and tripped. over a body lying across the road. We were very frightened. He was a soldier, so we decided to try and move him on to the pathway. As we were struggling a voice boomed out of the darkness, "leave him alone, that man is dead drunk". The voice was from a soldier on guard duty, just inside the gates ofLangley House. As it was very dark we had not noticed him, but now could just see his face. We quickly dropped him, and ran down the lane to catch the 'bus.

As time went on, the Germans bombed London, Coventry, Hull, York and many other cities. We could feel the vibrations when York was bombed; at times when the planes made a heavy droning sound, we knew they were bombers.

One night during late summer my boyfriend and I were walking over the moors. When we got to The Eaves, a home guard challenged us, and asked for our names. We both gave the same surname. He just said "brother and sister, forward" so we continued on our way, down towards Low Hill Chapel. As we were walking down we heard the droning sound of the bombers, and we saw them occasionally through the clouds. They seemed to be circling Hope Hill. We hurried along but before we reached home, we heard bombs exploding somewhere on the far side of Baildon, but could not see anything. We made our way down Salisbury Avenue to the Bank Top where there is a very good view of Leeds, Shipley, Bradford and the surrounding area, and immediately saw that a part of Bradford was on fire. A lot of damage was caused, luckily it never happened again in our area.

The Tale Of Three Little Pigs.

by Norman Robinson.

Around 1943 my brother-in-law and I, both unfit for the forces, decided we would keep pigs, one for each family. To do so we had to keep one for the government and then we could have rations of a sack of meal and a sack of potatoes for two pigs. The potatoes were dyed purple so no one would eat them! These rations had to last for a long period, so you were very short of food, and when a pig is hungry it screams at the top of its voice. People used to think you were killing them. They would start screaming around midnight as by then they were very hungry and we hadn't finished preparing their food. We didn't have time to collect wood and scraps of food, prepare and cook their food until after 9.00pm. We didn't get home afier feeding the pigs until 1.30am!

We had found an old set pot which we built into a stove with a fireplace underneath. The sty was made of corrugated sheets and a concrete floor. The straw we bought in bales from a farm. All the wood for the fire was collected from under the hedges or we broke branches from trees (just one or two), orange or apple boxes anywhere we could find some wood (coal was rationed).

The trouble started when we went to a farm to buy three little pigs that were ready to leave their mother.

We took three sacks to carry them in as we had to cross several fields. The pigs had been kept in a small hut with their mother and the farmer caught them for us. We fit one in each sack. I carried one, my brother-in-law took two. We only got a field and a half away and we couldn't hold them any longer, so I laid down on top of three pigs while my brother-in-law tried to get the van to us. It was the biggest fight I had ever had! They are shaped like a bullet and with four feet going like mad, they can force their way forward right out of the sacks. I think I rolled over half of the field trying to control them. I was dead beat by the time the van came. We loaded them up into the, van and took them home to their new sty.

A day or two later we decided to give them a bit of exercise, so as we rented a field, we let them out after first checking that the outer edges of the field were safe. The trouble started when we tried to get them back into the sty! They had no intention of being fastened up! When you cornered one, it just charged you and forced your legs apart, sometimes knocking you over. It took two hours to get all three back into their sty. The next time we decided that we would wait until they were hungry before we let them out. They came back very quickly when you rattled the food bucket!

On one occasion they all got out of the field and into several people's back gardens. It took half a day to get them back - luckily this happened on a Sunday morning!

When they had reached a certain weight, which as we had no scales in order to weigh them we had to make a guess, they were sent to Leeds to be killed and cut up I into joints or hams. These hams were hung in the staircase, being the coolest place for them.

Everybody was your friend at this time, all wanting a piece of pork or ham! We did this for two years but it was very hard work and when I was put on nightwork 12 hours, 6 days a week we had to get rid of the pigs!

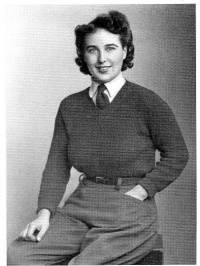

My Three Years in the Women's Land Army

by Betty Taylor (nee Giles)

With no experience of farm work, but a great love of animals, I enlisted with enthusiasm.

My day started at 7am. delivering milk around Charlestown, armed with a large can and two measures, a pint and a gill.

Early afternoons were usually spent in the fields hoeing, muck—spreading etc. Then it was time to fetch in the cows from a field half a mile or so away, for milking. This could be a hair—raising experience, as the route was along a main road, where at anytime an Army convoy was likely to appear. Cows being cows, were soon moving in and out amongst the lorries, to the great amusement of the soldiers, and the greater embarrassment of this Land Girl! When I eventually got them all into the milking shed that was a job I really enjoyed — the warmth and quiet was Heaven!

One afternoon, instead of being dispatched to the fields, I was told to take Bob, a very large Shire horse, along the main road to the blacksmith, to be shod. I had no experience with horses, so I was given the end of a rope to which he was attached and told to hang on! As it was just after Easter, Bob had been resting for a couple of days and consequently was very frisky! Every time a vehicle overtook us his back legs went up in the air and it took all my strength to hang on to the rope! A road—sweeper saw us and came across to advise me to cross over the road and face the oncoming traffic, which I did, but it didn't improve matters. I was very happy to see the farmer's son draw near in his van and take over!

Kath's Memories

by Kath Truelove

1939 was going to be a wonderful year in my mind; I became engaged on my 21 st birthday, 16th May. We looked forward to getting married in May 1940. At that time I was working at Matthias Robinson‘s in Leeds. My fiancé also worked in Leeds. I lived in llkley and he lived in Bradford. We both had to travel a long way to work.

I worked 48 hours per week for 25 shillings. I finished work at 6.30pm and 8pm on Saturdays. Life was good, but things changed on the outbreak of war.

We were visiting my grandparents in York, sitting in- the garden in the sunshine, when the news at 11am was given over the radio that we were at war with Germany. My mother cried and my father said it would be over in a year. We had a slow journey home not expecting all the streetlights to be out. We were told by the police to use only sidelights.

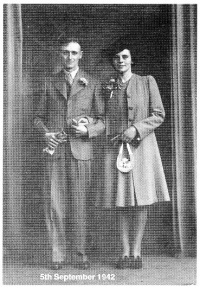

My husband-to-be wanted to get married straight away. We bought a new house in Eccleshill, the fireplaces had to be fitted and every room needed cleaning. A woman scrubbed seven floors for us for 2 shillings and six pence. After getting married my husband joined the army. I felt very lonely. However, I started a new job at the Post Office in Forster Square. I enjoyed four happy years in the Post Office. A lot of my friends had husbands or boyfriends in the forces so we used to swap our hours ofwork to fit in with home leave. We had to work compulsory overtime in Valley Road Sorting Office three nights a week from 7pm—9prn. After finishing work we used to sing "The White Cliffs of Dover" "When the Lights Go On Again". The shift always ended with "Jerusalem" or "Land of Hope and Glory". My wages had gone up to £3.10 shillings per week and 21 shillings Army pay. My husband was in India for two and a half years before returning home.

We had 50 happy years of married life.

Memories of Hawksworth village near Baildon

by Molly Wilkinson

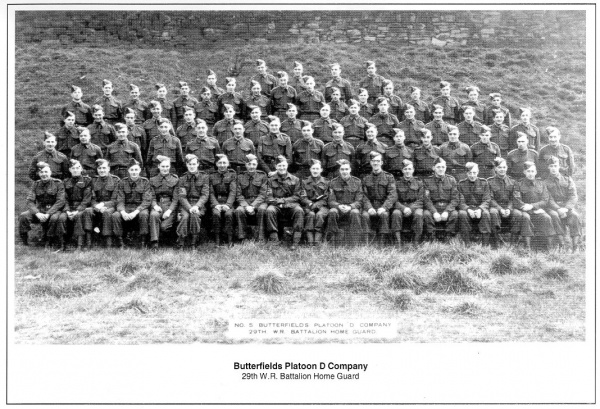

For the duration of the war some of the Butterfields' battalion of the Home Guard (of which my father was a member ) were based at Reva Reservoir in a caravan hidden away in a quarry behind "Reva House". I saw one of them rifle in hand, by our telephone waiting for messages. During one night when the sirens sounded we were in the air raid shelter that my father had made when we heard gunfire and explosions from bombs dropped on Hawksworth Golf Links. An unexploded one was defused next day after evacuating nearby properties. The German aircraft had mistaken Reva for Yeadon Tarn which had been emptied of water to protect the Munitions factory. I remember being at school when the siren sounded and we were taken to a shelter provided by Mr Gaunt of Hawksworth Hall. We read a little and did some singing and then the "all-clear" went. My parents were in the Civil Defence. We practiced wearing gas masks in a mobile gas-chamber brought to our village. I was only five years old and I was terrified because I thought we were going to be gassed. Baildon Church bells on V.E.Day were the first I remembered hearing as they floated over the valley to my home.

The Decontamination Centre

by Molly Wilkinson.

The decontamination centre for Baildon was built on Cliffe Avenue and manned by the A.R.P. and Civil Defence.

My father—in-law was in the A.R.P. and was Superintendent in charge of the building, which was their base. At one time it was stocked with clothing and footwear to distribute to Channel Island refugees who were brought to Baildon during the war.

There were garages at the back of the building which housed Civil Defence ambulances and one was kept at the side of the building. On the occasion of the worst Hull Blitz a convoy of these ambulances went to assist with the injured and killed people of that city. My father—in-law was one of these drivers and he told us all that he had never seen anything like it in all his life. The houses and other buildings were reduced to rubble and there were many casualties. It was a terrible sight.

After the war the building was used as Sandals School Kitchen and Canteen. The scholars went there for their dinners for many years until a portacabin within the playground was acquired. It was closed for some time after this until it became the home of Baildon Link Community Centre offering advice and guidance to the area and a place to meet.

Life at Crook Farm Recalled

by Marjorie Gardiner (nee Lancaster)

During the war my father owned Crook Farm on Baildon Moor. This meant we were high up, about 1000ft. above sea level, and could see for miles. We had a bird's eye view ofthe fires and destruction that went on in Bradford - and Leeds. We were above the sounds of the anti-aircraft guns and we could see as far away as Liverpool and watch the bombing and the fires. We could make out barrage balloons over the Blackburn area. We heard the heavy drone of the Lancaster bombers setting off on their missions of destruction and thought about where they were going.

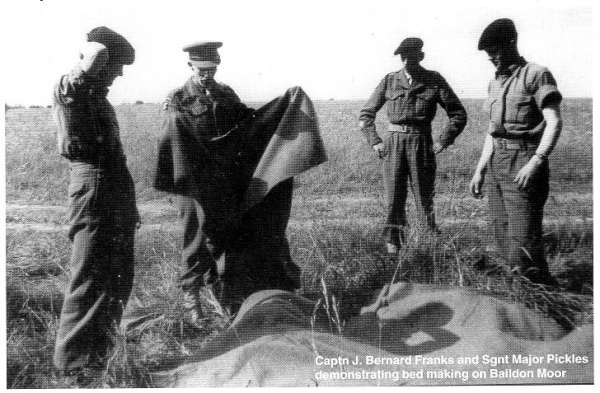

My father was in the Home Guard and it was his responsibility to guard the properties on the moor. He used to get very upset when the heavy military vehicles churned up the paths. The army practised a lot on the moor.

The eerie sound of air raid sirens came filtering through the valley and I remember one night my mother dragging me out of a warm cosy bed to go into a cold, damp, dark cellar which was our air raid shelter.

I also remember the very strict rationing we had to endure. Mother was very good at making ends meet. For instance when she made a meat and potato pie she would say "Whoever finds the meat gets the prize." This would have been when my brother Dennis came home on leave prior to going abroad to India and Singapore with the Royal Corps of Signals. (photo)

She listened to the wireless and liked Tommy Handley in I.T.M.A. She heard Winston Churchill inspiring all of us to carry on with all the tasks ahead and encouraging us all to keep our spirits up in spite of all the hardships we had to endure.

I used to go to school with my gas mask and we practised bomb drill and taking shelter. I was lucky and could go home every day; many children were evacuated away from their homes and families.

The lovely Hope Farm Woods (which included some rare trees) had to be chopped down for the war effort. The work was done by the prisoners of war from Slovakia. The timber was sent to Hull but was bombed at the docks by the Germans, it seemed so tragic.

A Schoolgirl's Recollections

by Gladys Burn

It was the end of the school holidays when war was declared, on Sunday 3rd September 1939 at 11am. We reported to Sandals School on the Monday morning but as we had no safety precautions (paper stuck on the windows to stop the glass flying or air raid shelters) we were sent home again. We enjoyed this as it put about two weeks longer on the summer holidays.

All good things came to an end, back to school we went to find our playground smaller as a gang of workmen were putting up the shelters. Once they were finished they were covered with soil. The only way into them was a bit like going into an igloo and once inside it was very dark until someone lit the oil lamps. We practised air raid drill and when our headmaster, Mr Varley, blew his whistle we all had to run to our allotted shelter. A roll call was taken and when he was satisfied that we were all present and correct we could go back to our classrooms. By this time half of the lesson had gone. I was very glad about this, especially when it was a subject I didn’t like such as English or History.

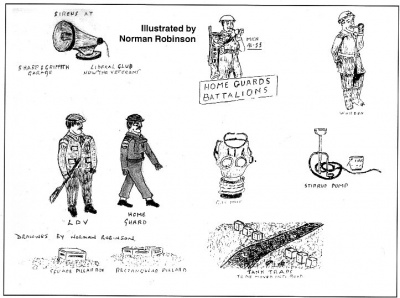

The day came when the army arrived on the moors (I have been told it was the 5th Duke of Wellington’s); they brought with them one small gun and a searchlight. You would have thought it was Carnival time the amount of people who went to see "The Military Camp" on top of the moor. If you go on the moor today you can still see where the two military defences were placed. We also had two concrete blocks built across Northgate, leaving just enough room for one car to get through on the road and one person on the pavement. In the event of an invasion there was a barbed wire barricade to put across the opening.

A short time before war broke out we were all issued with gas masks. Babies had a different type to adults; they were placed inside and it had to be manually pumped. Toddlers had red ones with big eyes and faces like Mickey Mouse etc. There had to be some way of raising funds to help pay for the war. Shops were opened on the lines of today's Save the Children and Oxfam. Then we had Spitfire Week; a Spitfire was brought to the village to show what money was spent on.

Someone thought of giving concerts so we had the Strathallan Kids and the Collier Lane Sunbeams. They raised £500 between 1940 and 1945.

This is a list of rations 2 years after the war; (in ounces per week) butter 4, margarine 3, lard 1, tea 2, bacon 2, cheese 1 and 8 points for bread, flour, cake and buns per month, 12ozs soap per month, 12ozs to 16ozs sweet coupons per month. Clothing coupons were needed for sheets, towels, curtains and shoes as well as clothes. Children did get a few more than adults to allow for growing. Most goods were available if you had the coupons. Shops were not allowed to wrap anything so you had to bring your own bags and paper. People helped each other out and exchanged goods according to their needs and tastes. Similar things happened with furniture as this was also difficult to obtain. You had to have dockets and you only got them ifyou were getting married or had been bombed out. As the East Coast and South Coast were "out of bounds", it was usual to stay at home for your holidays and have days out. Baildon got quite busy at weekends and Bank Holidays when lots of people brought picnics to have on the moor. They could buy jugs of tea from The Strawberry Gardens and Low Hill Chapel by leaving a deposit on the crockery at the time of purchase and having it re-paid on return. At the end of the day the queues for the buses stretched from the stocks to the Malt Shovel but the ten minutes service kept it moving.

I started work in 1940 at a ladies outfitters. We had to blackout the windows each evening when we shut; it was quite a feat with such large windows. I changed to munitions work at Rennison and Pratt (Engineers) Baildon Green Mills on V.E.Day 8th May 1945. (I kidded myself that the Germans had heard about me and decided to give in.)

As we all know our hardships did not end for many years.

The Rushworths' Reminiscences

by Phyllis Rushworth

I was sixteen and lived in Leicester when war was declared in September 1939 and was employed as a shop assistant selling materials by the yard. We also had a dressmaking department where I was called upon to help when they were very busy. The shop was near the centre of town and one morning when I got to work I found the shop windows had been shattered and the window display of materials ruined; also the shoe factory at the back of the shop had been hit with incendiary bombs and had been burnt out. The shop manageress had moved house the day before and came to tell us that her new house had been destroyed and they were having to go back to the old house.

Like most other people I didn't know what to expect when the war started and the first time we heard the air raid siren we gathered up the dog and dashed to the bottom of the garden where an air raid shelter had just been erected. We were waiting for the concrete floor to be laid but had taken some old chairs to sit on. We had settled ourselves down wondering what would happen next when our neighbour, with whom we had to share the shelter, appeared carrying the bird in its cage, leapt over the fence dressed only in his underpants. By the time the "all—clear" sounded our chairs had sunk nearly down to the seats in the mud at the bottom of the shelter. Soon after, the concrete floor was laid and we made the shelter quite comfortable. During the raids on Coventry we could clearly hear the bombing. When there was an alert my mother would report to the first aid post where she worked on the switchboard and my two eldest brothers helped with Air Raid Precautions (A.R.P.) until they went into the forces.

It was my job then to look after my youngest brother and my youngest sister. We would go to the school air raid shelter which was just across the road from our house and take blankets and a flask of something hot to drink. At least over there we had someone to talk to and it helped to pass the time until the "all—clear" had sounded.

At the age of eighteen I had to register for war work. I really wanted to join W.R.A.F. but my mother was not too keen on me going away from home as my brother was already serving in the forces, so I started my war work at Vickers Armstrong’s as a riveter making Spitfire wings. I had to work a month on dayshift and a month on nightshift which was a twelve hour shift from 8pm to 8am. I found the nightshift very hard to get used to and it was affecting my health so I was advised to apply for a transfer to another factory where there was no nightwork. The factory was in a hangar on the edge of an R.A.F. training field and I was issued with a pass to allow me entry to the area. I worked in the stores and the Spitfire was fully assembled there, the wings coming from the factory where I had previously worked. The aircraft was then taken out by a test pilot for a very thorough testing.

In May 1943 there was a Wings for Victory Week. This was organised to raise funds for the R.A.F. A float carrying a Spitfire wing was supplied by the head office at Castle Bromwich and several girls were chosen to travel on the float to some ofthe surrounding villages of Leicester. We had to demonstrate how the skin, as we called it, was riveted onto the frame of the Spitfire wing.

The float was followed by an Air Force Band and Air Force Personnel. Afterwards those of us who travelled on the float were sent a photograph and a word of thanks from head office. We all enjoyed our unusual day out. The factory closed after the war finished in 1945.

One night during the war I had gone to a cinema in Leicester to see a film, when an air raid siren sounded. We were all told by the manager not to leave the cinema for our own safety but by the time the film finished the "all—clear" had not been sounded so we were asked to stay put and another film was shown. It was "King Solomon's Mines", due to be shown the following week. When the second film finished we were allowed to leave and fortunately the buses were still operating although it was very late.

There was a searchlight positioned at the top of the road where I lived. This is where I met Fred whilst taking my dog for a walk on the park near the searchlight site. One night an enemy aircraft fired down the beam and bullets were found next day in the school playground, just yards fiom where we lived. Fred was only at this site for a short time after we met, then he was sent to another area. We married when he returned from abroad when the war was over and we came to live in Baildon.

Fred's Experiences

by Fred Rushworth

When I got my calling up papers I found that Benny Marsden had also got his to the same place. It was Pollington Barracks at Snaith, near Goole.

Benny's family, my mother and I had a few get-togethers, seeing that we were going to the same place. As we came out of Marsden's house on the night before we were due to go, Benny's mother said to me "Look after our Benny". I was older than Benny so his mother must have thought I could keep an eye on him, although Benny was married and had a little girl. We arrived in Pollington and reported in. The next thing was to get kitted out. We had our ground sheet opened out and as we got each item it was put on the ground sheet. The next thing we were allotted to our huts which would be our home for several weeks. I could find no sign of Benny, when I did he was in the NAAFI sat behind a pint of beer. I really did not have to look after Benny and we were now in the 5th Duke of Wellington's Regiment, 373 Battery RA.

We had Pollington RAF next to our camp. Wellington bombers were used. They were wonderful planes and were out every night on raids, weather permitting. We got on very well with the pilots and ground crew. Benny and I had not been at Pollington much more than a week and he was home sick, so he said, "Let's hitch hike home". We had a pass on a Saturday from 12 midday until 12 midnight. He said, "My cousin who lives in Bingley will run us back to camp". We got home after several lifts but when we wanted to come back to camp, his cousin did not have the petrol for so long a run. It was panic stations, Benny's parents, his Auntie Carrie, Archie Pemberton and my mother paid for my fare back. We managed to get Black and Gold taxis to run us back to camp, just at the stroke of midnight. We were saved from going on a charge. Benny and I were split up and did not meet again until after the war.

One sad thing was that my pal, Fred Crabtree, who was called up just before me did not return from the war he died when his unit was on retreat from the Japanese. They had dysentery, were short of food and water and having to force march, they were exhausted. When they stopped for rest Fred did not get up; he had died from the terrible conditions. His sister Lily told me that Fred was buried on a riverbank somewhere out there. Lilly put a memorial in the paper every year until she passed away. On his last leave he called to see his mother and said "I'm going on a cruise". It was of course his embarkation leave.

We have paid three visits back to Pollington. On the first two the camp was still there in perfect condition with the barrack square, where we did our marching. On the last visit, all that remained was a square yard of tarmac. That was all that was left of the barrack square; the rest was industrial estate. RAF honington was also gone and the land returned to farming; it is all now a memory.

I finished up in East Africa. We were due to go out to Burma with African troops but the atom bombs were dropped in Japan. That of course was the finish of the war and did save as going to Burma; we were very lucky. Hull was the most consistently bombed town during the war. Every night weather permitting we got this information with being on searchlights, we got reports where raids had taken place. The searchlights at the start of the war were poor; we were lucky if we did illuminator target. It was sonar location. Later we got new equipment which was SLC and Radar controlled. We could then illuminate most targets, the lamps were 150cm against the 90cm old type. It was a big step forward and good for our morale.

It is all memories now. Some good and some bad. A lot of chaps I knew did not come home and we must not forget the civilians. What an awful time some of them had being bombed out and so many killed

My War

by Sheila Edwards

The outbreak of World War 2 coincided with the start of my teaching career — I had qualified that summer and had been assigned to a Senior school in South Birmingham, actually brand new and virtually overlooking the airport. I duly presented myself on, I think, August 28th, to join a staff of 11 (5 men, 5 women, and the head master) all assembling to work together for the first time. At the end of the first week the Head, who had served in WW1 and was on the Air Force Reserve as a 'Terrier', was called up. (The last I heard of him was that he was part of a balloon barrage squad.) This left us in the charge of the Deputy, Miss Williams, who was only in her 20s. War was declared on September 3rd and evacuation plans were put into operation. Our school was deemed 'neutral', which meant we were not evacuated. City schools were closed and evacuees sent into "reception" areas. The area next to ours (Warwickshire and Worcestershire) was a reception area. Our neighbouring Junior School was requisitioned as a possible casualty hospital so the children from there were moved to our school; we all went onto half time attendance. Teachers were instructed not to sleep outside the city boundaries so as to be available for instant evacuation or any other war duties. This worked reasonably well for the first term, but January 1940 was exceptionally cold, the school central heating froze and we had to close whilst this was repaired. During the year our male staff were one by one called up. I don’t remember that we had any replacements. So our school of 'mixed' adolescents was in sole charge of 5 rather young female teachers. I had a class of forty eight 13 year olds!

That summer, my fiance (also teaching in Birmingham) received his call-up. Actually he went no further than Kidderminster, where he was drafted into a Pay Corps Unit housed in a dilapidated carpet mill. (He had been graded A1 apart from sight, so the war office in its wisdom allocated him to a clerical job!) Two years later he was upgraded and served the rest of his army life as an instructor in Driving and Maintenance in the RAC, after an assessment course. We decided to marry, and this took place on 3rd September (1st anniversary of the War) and I was to go on teaching. By this time the blitz had started. I remember going over to Kidderminster one Sunday and being caught in an alert as I left the bus in Birmingham on my way home. (I was in 'digs' in Shirley at that time.) In the first days of the blitz all traffic stopped so there was no alternative but to seek a shelter. At that time it had not been anticipated that raids would last long, certainly not all night. I finally arrived home at 6am with my landlady wondering where on earth I had been. I had watched, from the shelter, a very spectacular fire — the market hall had been set alight. Mrs Cooper had seen it from Shirley; even Gordon had, in Kidderminster. The raids continued into the autumn; as a civilian I felt the worst aspect was the sleepless nights as Shirley was surrounded with Ack-Ack emplacements. None of us was in much of a state to cope with lively youngsters although they themselves were also losing sleep. The night of the Coventry raid was very memorable. Shirley is half way to Coventry (from Brum) so we had some idea of what was afoot.

Our turn came towards the end of November. On my birthday we had spent the day shepherding the children into the shelters as we had several alerts; finally we discovered that the playground had been liberally sprayed with shrapnel so didn’t run for shelter any more.

One night "Jerry" managed to hit the aqueduct which brings water to Birmingham from Wales; as so much of the city was without water it was decided upon immediate evacuation for the children. I found myself in a little mining village called Nant—y—Moel in South Wales, already crowded with evacuees I may say. Gordon had become concerned for my safety earlicr, and had persuaded me to resign. (On being married I was really no longer eligible to teach but had been added to the Supply list and in fact had continued as before.) My notice expired at the end of November so I returned from South Wales, picked up my things in Birmingham and joined Gordon in Kidderminster. I never went back to teaching there but did some voluntary clerical war work addressing ration books and other "literature" for example.

Our first baby arrived in 1942. I came home to "Mum" for the birth, and also spent time with her later when Gordon was drafted into the RAC. He had various spells at different depots, Brecon, South Wales, Barnard Castle, and Bovington. I was able to join him there, and we had 'digs' with a farm worker and his wife in a thatched cottage with no mod cons at Wareham, Dorset. I had my second child at Poole hospital. Just before the invasion Gordon was moved to Farnborough, Hants. I stayed on at Wareham for the time being. The area became "no go" in the few weeks before the invasion which meant all movement was very strictly controlled; even letters from Gordon were censored; mine as well probably. Gordon and a colleague found a house to rent in Camberley, so we moved in together. Immediately before the invasion there was a tremendous burst of activity, and I remember all the vehicles appeared. to be marked with a star regardless of ' whether they were American or not. In Dorset we had been the preserve of American troops, in Hampshire it was Canadians.

When Gordon had a leave we spent it alternately at Bradford with my parents, or in Cockermouth, his home. In Cumberland life seemed so peaceful, I don’t think his mother really knew what rationing meant. There were of course very few if any visitors, and very little transport but we did venture as far as Buttermere one day as a bus ran weekly to transport farmers to Cockermouth market on Mondays. We had the lake to ourselves. Gordon was demobbed in October 1945; he had an early release as teachers were regarded as essential to get education re—organised. He found a post in Bradford (we couldn’t find anywhere to live in Birmingham.) In Bradford we were able to rent my mother's home as she had moved to what had been our weekend bungalow at Cottingley, and let our house near Five Lane Ends. It happened to be available when we needed accommodation.

So that was "my war"; no exciting time with the forces but quite a varied experience as a civilian in various locations.

The Effects Of WW2 On My Life

by Konrad Ronkowski

On the 1st September 1939, the German Army attacked Poland and embroiled the whole world in a conflict on a scale hitherto unknown to mankind. Millions of people lost their lives. Families and whole nations were torn apart, the well—equipped German forces conquered and occupied most of the Continent of Europe. I was fourteen at that time and just finished my primary education. My further studies had to be abandoned; I was taken to work on a German farm instead. The conditions there were rough to say the least. Our living quarters were in a bug-infested wooden shack, where the cold autumn wind had free access and played its mournful tunes through the cracks and gaps of the walls. Survival became a priority and hope the fuel to carry on.

The news about the formation of a Polish Army in Great Britain gave birth to dreams of escape and after the allied landing on the 7th June 1944 in northern France the dreams became reality. I set foot on English soil in late September the same year and transferred to Scotland where I joined the 1st Polish Armoured Division led by General Stanislaw Maczek under British Command. After a short intensive live ammunition training we were posted to Crieff to await our transport to Belgium. Shortly after Christmas 1944 we arrived at a small town near Brussels where the old garrison's barracks became our abode for the duration of our stay there which turned out to be a happy one. I vividly remember our early morning marches to the training ground, singing to the rhythmic steps of over two hundred pairs of boots stamping on the cobbled streets of the town, where old and young dwellers clapped and cheered through the opened windows of their abodes. Merriment filled the air now where only a short time ago the rattle of machine gun-fire and exploding artillery shells sent the people scurrying for shelter. The time passed quickly by. Our combat proficiency completed, we were ready and eager to join the front line troops in Holland. The night before our departure a German V2 rocket, on the way to Great Britain, malfunctioned and dropped in the vicinity of our barracks. The blast demolished part of the building and buried me under the rubble. I managed to free myself bruised but otherwise alright; I reported back to my unit. My comrades greeted me warmly, realising earlier reports of my death were untrue. Last minute checks and loading of essentials completed, we moved under cover of darkness out of the town.

A few hours later we were passing masses of destroyed and abandoned German Army equipment, burnt out tanks and some allied lorries with Polish markings on them stood witness on the roadside of the heavy fighting which the Poles encountered on their way to Maas where a 30-mile front was entrusted to their protection over the winter months. For a while we traveled in silence, then someone remarked "I wonder what is waiting for us at the end of this trip?" I quipped "Whatever is in store I should be alright; they can’t kill me twice".

With cautious advance we reached our destination the next day and after brief formalities we became front line soldiers.

The Spring Offensive, the final push against Germany, was about to begin. The 1st Polish Armoured Division took part in spearheading the attack and crossed the German border on 9th April 1945. After a short rest we returned to Holland to clear some isolated pockets of German resistance. On completion, we moved out of Holland through the flooded lowland depression region to capture Willhelmshafen, the German Navy stronghold. We entered from three directions on 5th May l945 two days before the German surrender and the end of the War in Europe. A week later we moved to the provinces, where I was given the opportunity to go to college and complete my education. On 10th May 1947 we were relieved by British forces and returned to Great Britain to be demobilised and prepare for civilian life through the Polish Resettlement Corps.

I was due for two weeks leave, the first week I planned to spend in Scotland visiting old friends and suchlike. The second week I was to spend with my friend Kazik in Yorkshire to help him find a job because he couldn't speak English. I was glad to help him. His fiancee, Anna, from a DP. Camp in Germany came to work in the textile industry in Bradford and they planned to marry the following summer. He needed employment and somewhere to live. Anna, through some friends, found him lodgings with Mrs Philips at a nearby village, Baildon, which we shared at a later date.

Kazik was waiting for me at the railway station and we caught the 61 ’bus to Baildon and had an interesting journey with a grandstand view from the top deck front row seats. The ’bus turned into Green Lane and slowed down to negotiate a sharp right hand bend. The hamlet of Baildon Green‘with flanking green meadows and the rugged Baildon Bank as a backdrop spread before our eyes creating a beautiful picture. We got off at the next stop and walked 200yds to Mrs Philips' house in Enfield Road. She greeted us warmly and I felt at home immediately. We had a chat with her and I interpreted for my friend, we were invited to have some refreshments and whilst doing so covered a number of topics. She told me that Mrs Shaw, who lived in the house across the back garden with her husband and four daughters, asked her for the room for Anna's fiance. I decided to go next day to thank Mrs Shaw for her good turn especially when I was told more about the daughters. The knock on the door was answered by a young girl dressed in green overalls and as she stood framed in the doorway our eyes met. I forgot the reason for our visit then her warm smile brought me back to earth. I introduced Kazik and myself and explained the purpose of our intrusion. She invited us to meet her parents, I thanked her mother, and we exchanged names. Our conversation flowed with case. On leaving, I whispered can I see you again? She smiled and nodded her head. The following day we spent looking for jobs and secured one for Kazik and one for myself. In the evening I went to see the Shaws again and conveyed our news of the day. Kazik and I departed to our units, got demobilised and three months later came back to live with Mrs Philips. I returned to the girl in the green overalls who ten months later became my wife. We settled in Baildon had three sons who now are married and have their own families. We are blessed with five granddaughters and two grandsons. It would be difficult for me to imagine finding a happier place for me to live.

There are a few other photos/images in the PDF version